A first-year emergency certified teacher, Mariam Starky, entered her 1st-grade classroom with wide eyes and a warm heart. Deeply committed to closing educational inequities, Mariam threw herself fully into her job, working late nights on a regular basis. But something was not quite working. The classroom was often chaotic, and she left feeling defeated every day. By October, she was not sure she could continue teaching.

I was assigned to be her instructional coach. We sat down for our initial meeting to discuss how we would work together, set goals, and prioritize our first steps. Almost immediately, Mariam started crying. “I am just not cut out for this,” she said.

“You are,” I replied. “And I am going to prove it to you.”

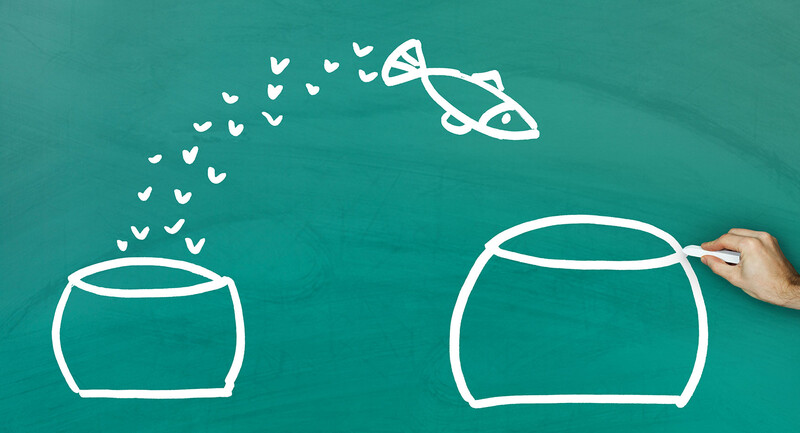

I knew I needed to model confidence to help Mariam see past her doubt and begin working toward her highest potential as a teacher. To help her realize her full capability, I needed to lay out a plan based on short cycle management, which would allow us to break big doubts into specific, concrete action steps and check in about them frequently.

Doubt and the 3

Coaching frequency matters because regular, skills-based feedback is correlated with teacher development, teacher retention, and student achievement (i.e. Bryk et al., 2015; Ingersoll & Smith, 2004; Walpole, et al., 2010). If a teacher had two conversations a year with a coach, generally there would not be enough feedback and accountability to result in significant professional growth. If possible, a coach should aim for one coaching cycle per week with a teacher, consisting of an observation and coaching conversation. This frequency is especially effective for beginning teachers who are often considered high potential and low skill. But once a week was not enough for Mariam. She needed “short cycle management.”

Short cycle management is characterized by increased frequency of touchpoints and tighter accountability to specified action steps. When does a coach know to shift to short cycle management? Short answer: Doubt.

Doubt causes teachers to question whether they will be successful in implementing an action step, which can lead to half measures, inconsistencies, and avoidance behavior. Undoubtedly (pun intended), doubt leads to slow growth or even stagnation as teachers fall back on ineffective practices. There are three main sources of doubt that help instructional coaches determine the need to shift from a typical weekly frequency to short cycle management:

- Doubt in Action Step: Coaching involves building skills through incremental, manageable steps. Each coaching cycle should allow the teacher to practice a narrow action step tied to evidence collected during observations. A teacher may say, “I’ve tried that” or “that won’t work with my kids,” indicating doubt in the effectiveness of an action step. The teacher may not even make an attempt at all.

- Doubt in System: A teacher may believe that the action step is effective but may doubt the school systems holistically. These systems could include discipline, curriculum, and even colleagues. A coach may hear things like, “I can do that but if Mr. Johnson allows phones, it will be an uphill climb,” “My principal doesn’t care about my lesson plans,” or “My kids are going to freak out if I make them write in math. They have never had to do that before.” Often, doubt in the system will limit teachers’ attempts at implementing an action step or prevent teachers from attempting it altogether.

- Doubt in Self: Lastly, a teacher may believe that other people can implement the action step effectively but doubt themselves. They may have a severe lack of confidence and need to be shown even the smallest level of progress.

Accountability Tools

Accountability does not necessarily mean an additional coaching meeting. While an additional meeting can be advised, a coach can get creative with accountability measures to maximize their time while still getting a positive outcome. Coaches can check in with teachers more frequently through accountability tools like:

- Lesson plan (or other planning output) turn in: “Turn in your lesson plan for Friday by tomorrow evening so I can give you feedback.”

- Photo evidence: “When you get your line procedure poster up after school, shoot me a picture of it.”

- Quick phone call: “Try out what we discussed today and then let’s hop on a quick phone call after school to talk about how it went.”

- Quick text message: “Text me after reading to let me know how it goes! I can’t wait to hear about it!”

- Written reflection: “I sent you an email with a reflection question in it. Send me your response by the end of the weekend.”

- Student work/exit tickets: “I’m not going to be able to make it in to see the result but collect a couple of examples from this lesson and stick them in my mailbox. I can help you analyze what the next step would be.”

- Live coaching: “I’m going to stick around for the next period to see how this move is working. I will pull you aside to give you some additional pointers.”

Often, teachers who engage in short cycle management are “in the weeds”; while decisions can be made collaboratively, choosing an accountability method is usually determined by the coach. Therefore, when choosing among accountability tools: 1) a coach must ensure the tool aligns with the action step that the teacher is practicing (i.e. select lesson plan turn-in for a planning skill), 2) a coach must consider their relationship and level of trust with the teacher, and 3) a coach must take into account the capacity (time, skill, bandwidth, etc.) of the teacher.

From Doubt to Confidence

Because of her severe lack of self-confidence, Mariam and I started short cycles early in our coaching relationship. I started with two coaching cycles per week, including some live coaching and quick phone calls on our commutes home. I collected as much evidence of progress as possible: quantitative evidence, student quotes, work samples, and photo evidence. Soon, I started to see an increase in her confidence, so I slowly shifted to weekly cycles. At the end of eight weeks, we reflected on our work. Mariam said, “You showed me that I was capable of doing this when I didn’t believe it myself, but it wasn’t just your opinion. You used evidence like how much time transitions took or how many students raised their hands.”

Given coaches’ and teachers’ limited capacity, coaches should leverage short cycle management sparingly. Identifying sources of doubt—in step, system, or self—can help coaches determine when to best double-down coaching efforts. Coaches can get creative with how to tighten accountability outside of increased coaching conversations, from using tools like photo evidence to providing examples of student work. For teachers like Mariam, short cycle management can make all the difference in keeping our highest potential teachers in the classroom.